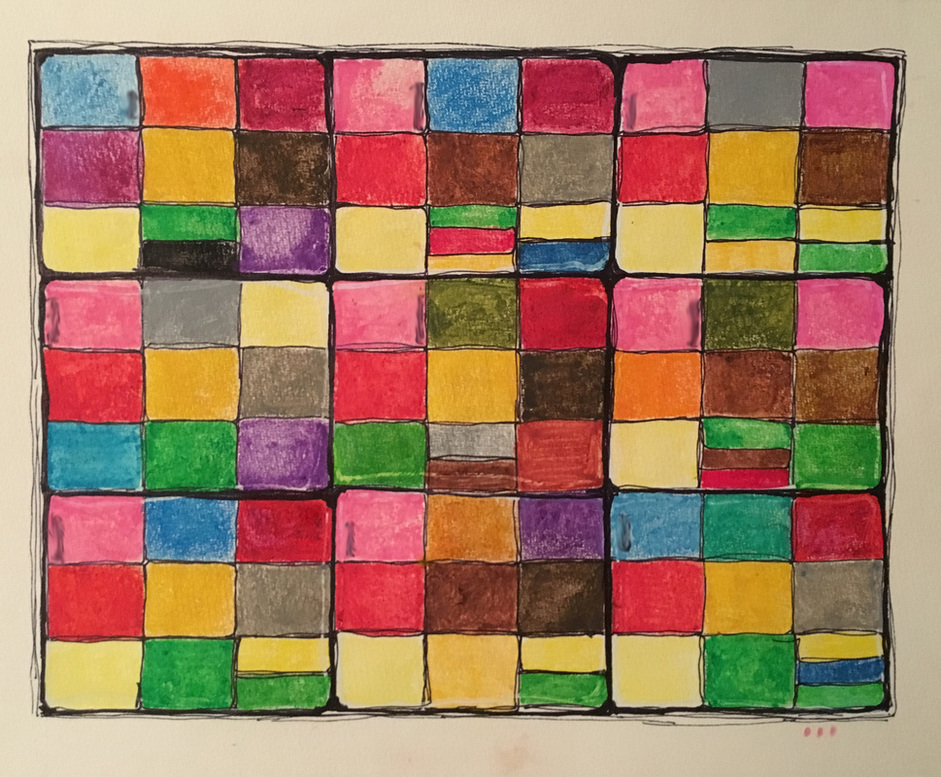

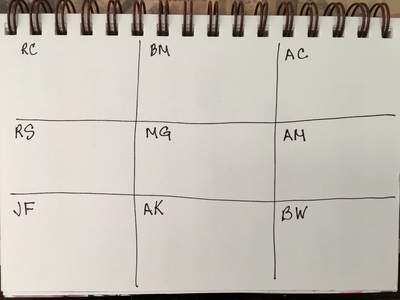

We have reached a point where almost everything we do with technology generates a point on our data portrait—purchases, downloads, directions, emails, phone calls, etcetera. Our data portraits are continuously being painted and refined. Should we be worried? If so, what can we do? How are contemporary artists responding? In response to my research I created a “data portrait” of our class. All information was gathered from posts made during our course. Names have been “blurred” to protect identities.

Globalization & Me - Data portraits

My addiction began after a diagnosis of kidney cancer. At first it was for medical reasons—tracking medication and measuring pain. As I continued to recover, my tracking addiction gradually started to grow and I found myself downloading apps to track walks, sleep, and moods. Eventually, I invested in a Fitbit and was able to bluetooth it to my computer. I could track exercising, weight, the calories I took in and the calories I burned, the food I ate and the amount of water I drank. It was sometime after this that I noticed the ads for exercise clothing, gym shoes, and diet supplements popping up in Google and on social media. It was clear I had a problem—my tracking addiction was creating a data portrait of what I did, what I was thinking, and where I was going.

In the digital age we live in, this is no surprise. Unlike traditional portraits, data portraits are not based on the human face. Instead, they are based on what is behind the face; the data we have accrued. These portraits represent the new global citizen, the one living their life connected to technology. The global citizen is constantly connected to computers, cell phones, tablets, and now watches. As Weiskopf (2014) explains, in all our networked interactions we are casting “a ‘data shadow’—an outline filled in by accumulated transactions with social, government, and commercial websites, emails, texts, and swipes at ATMs and purchase points” (para 5). We are charting out our activities on social media and through everyday activities. We are reading books on Kindles. We are watching movies on Netflix. We are paying for tolls and airport parking with E-ZPasses. We are using debit cards to buy our groceries and our gas. We are using Google for directions. Urist (2015) discusses how Frick (2015) goes so far as to say, “Amazon knows how fast you finish a book, and whether you’re a cheater and skip chapters or read the ending first” (para 10). We have reached a point where “almost every human interaction with digital technology now generates a data point—each credit-card swipe, text, and Uber ride traces a person’s movements throughout the day” (Urist, 2015, para 3). Our data portraits are continuously being painted and refined.

Currently, many people have concerns with the government monitoring our data portraits. However, data portraits provide information to people other than the government. Companies are tracking what is of interest to them and others are gathering personal data and selling it to industry research outfits (Zwedling, 2013). Should we be concerned? And if so, what can we do about it? We could cut off our devices and pay for everything in cash. Realistically, this is not going to happen. Even if it did there would still be data points we could not prevent. According to Zwedling (2013),

While there are some measures you can take to prevent the government and others from monitoring your data and movements,

much of what we do online and in public spaces can be used, sold and shared to create a remarkably detailed portrait of our lives.

(para 21)

Within the field of contemporary art, there are a few artists exploring the subject of visual data portraits. One such artist is Hasan Elahi, an

American associate professor at the University of Maryland. After 9/11 Elahi was detained at Detroit airport as a result of an erroneous tip given to law enforcement. After going through six months of FBI interrogations and nine lie-detector tests, Elahi was finally cleared (Urist, 2015, para 13). The experience changed his relationship with personal information and inspired him to create the website, TrackingTransience. Elahi now posts photos of his minute-by-minute life. He wears a GPS device that tracks his movements and continuously updates his site’s live Google map. Elahi states, “I’ve discovered that the best way to protect your privacy is to give it away” (Thompson, 2007, para 4).

Another artist investigating data portraits is Nicholas Felton. Known for weaving measurements of collected data into artworks made up of graphs, maps, and statistics, Felton’s work is part of a permanent collection at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. While a majority of his pieces are self-portraits reflecting an entire year’s activities, he has also crafted data portraits of family members. In addition to making art, Felton creates apps to help others graph and record and visualize their own data.

Laura Frick looks at data portraits in a different way. She believes that technology has the ability to disrupt the art world, as we know it today. While Elahi's work is ongoing and Felton may spend an entire year or longer on each piece he creates, Frick believes that technology can crank out data portraits in no time that are beautiful, personalized, and tailored for the individual. With the stroke of a key, portraits can be designed as an abstract or as a realistic painting. They can have the appearance of a landscape or as spray-paint graffiti. With 3D printer technology, a data portrait can even include texture. Frick’s (2016) opinion on “creepy surveillance” is to “take back your data and, turn it into art” (para 1).

Kristin McIver is an Australian-born, New York based data portrait artist. According to McIver (2015), her work celebrates individuality, “while also questioning the pervasive corporate surveillance that now plagues modern living” (para 6). She translates facial recognition data, generated by computers, to obtain individual face prints from social media websites like Facebook. McIver believes that each face print contains a unique data string. She then uses the data string to create geometric abstract pixel-like data portraits, vertical gardens, and sound compositions.

As an art educator surrounded in the classroom with students who are connected to the world through technology, the issue of data portraits needs to be addressed. Students need to understand that their Google searches, Tweets, Instagram pictures, Snapchat stories, and Facebook posts, are painting a data portrait. They are revealing to others who they are through their connections online. As their teacher I feel it is important to share the information I have researched and the work of the above mentioned data portrait artists. We could discuss the importance of considering the type of information that is appropriate to share. There are a number of questions we could address. What are the things you want other people to know about you? What are the things that you do not want them to know? Are you different in person than the online persona you are creating? Having students create their own data portraits using only information they have shared online could open up even more discussions and possibilities. Or they could create a data portrait of a friend using a pseudonym or of a sports figure or a musician. While I feel I have only touched the surface of this issue, I believe this is a start in the right direction in helping my students realize the importance of understanding data portraits.

References

Felton, N. (n.d.). Biography. In Feltron.com. Retrieved from http://feltron.com/about.html

Frick, L. (2016). The future of data about you. Lauri Frick. Retrieved from http://www.lauriefrick.com

Kristin McIver: data portraits. (2015). Royal projects: contemporary art. Retrieved from http://royaleprojects.com/exhibitions/kristin-mciver-data-portraits/

McIver, K. (2016). The Selfie Project. Kristin McIver visual artist. Retrieved from http://www.kristinmciver.com/display.asp?entityid=10235

Thompson, C. (2007, May 22). The invisible man: an FBI target puts his whole lifonline. Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/2007/05/ps-transparency/

Urist, J. (2015, May 14). From paint to pixels. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/05/the-rise-of-the-data-artist/392399/

Weiskopf, D. (2014, July/August). Picturing the self in the age of data. Art papers. Retrieved from http://www.artpapers.org/feature_articles/feature2_2014_0708.html

Zwerdling, D. (2013, September 30). Your digital trail and how it can be used against you. NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2013/09/30/226835934/your-digital-trail-and-how-it-can-be-used-against-you

In the digital age we live in, this is no surprise. Unlike traditional portraits, data portraits are not based on the human face. Instead, they are based on what is behind the face; the data we have accrued. These portraits represent the new global citizen, the one living their life connected to technology. The global citizen is constantly connected to computers, cell phones, tablets, and now watches. As Weiskopf (2014) explains, in all our networked interactions we are casting “a ‘data shadow’—an outline filled in by accumulated transactions with social, government, and commercial websites, emails, texts, and swipes at ATMs and purchase points” (para 5). We are charting out our activities on social media and through everyday activities. We are reading books on Kindles. We are watching movies on Netflix. We are paying for tolls and airport parking with E-ZPasses. We are using debit cards to buy our groceries and our gas. We are using Google for directions. Urist (2015) discusses how Frick (2015) goes so far as to say, “Amazon knows how fast you finish a book, and whether you’re a cheater and skip chapters or read the ending first” (para 10). We have reached a point where “almost every human interaction with digital technology now generates a data point—each credit-card swipe, text, and Uber ride traces a person’s movements throughout the day” (Urist, 2015, para 3). Our data portraits are continuously being painted and refined.

Currently, many people have concerns with the government monitoring our data portraits. However, data portraits provide information to people other than the government. Companies are tracking what is of interest to them and others are gathering personal data and selling it to industry research outfits (Zwedling, 2013). Should we be concerned? And if so, what can we do about it? We could cut off our devices and pay for everything in cash. Realistically, this is not going to happen. Even if it did there would still be data points we could not prevent. According to Zwedling (2013),

While there are some measures you can take to prevent the government and others from monitoring your data and movements,

much of what we do online and in public spaces can be used, sold and shared to create a remarkably detailed portrait of our lives.

(para 21)

Within the field of contemporary art, there are a few artists exploring the subject of visual data portraits. One such artist is Hasan Elahi, an

American associate professor at the University of Maryland. After 9/11 Elahi was detained at Detroit airport as a result of an erroneous tip given to law enforcement. After going through six months of FBI interrogations and nine lie-detector tests, Elahi was finally cleared (Urist, 2015, para 13). The experience changed his relationship with personal information and inspired him to create the website, TrackingTransience. Elahi now posts photos of his minute-by-minute life. He wears a GPS device that tracks his movements and continuously updates his site’s live Google map. Elahi states, “I’ve discovered that the best way to protect your privacy is to give it away” (Thompson, 2007, para 4).

Another artist investigating data portraits is Nicholas Felton. Known for weaving measurements of collected data into artworks made up of graphs, maps, and statistics, Felton’s work is part of a permanent collection at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. While a majority of his pieces are self-portraits reflecting an entire year’s activities, he has also crafted data portraits of family members. In addition to making art, Felton creates apps to help others graph and record and visualize their own data.

Laura Frick looks at data portraits in a different way. She believes that technology has the ability to disrupt the art world, as we know it today. While Elahi's work is ongoing and Felton may spend an entire year or longer on each piece he creates, Frick believes that technology can crank out data portraits in no time that are beautiful, personalized, and tailored for the individual. With the stroke of a key, portraits can be designed as an abstract or as a realistic painting. They can have the appearance of a landscape or as spray-paint graffiti. With 3D printer technology, a data portrait can even include texture. Frick’s (2016) opinion on “creepy surveillance” is to “take back your data and, turn it into art” (para 1).

Kristin McIver is an Australian-born, New York based data portrait artist. According to McIver (2015), her work celebrates individuality, “while also questioning the pervasive corporate surveillance that now plagues modern living” (para 6). She translates facial recognition data, generated by computers, to obtain individual face prints from social media websites like Facebook. McIver believes that each face print contains a unique data string. She then uses the data string to create geometric abstract pixel-like data portraits, vertical gardens, and sound compositions.

As an art educator surrounded in the classroom with students who are connected to the world through technology, the issue of data portraits needs to be addressed. Students need to understand that their Google searches, Tweets, Instagram pictures, Snapchat stories, and Facebook posts, are painting a data portrait. They are revealing to others who they are through their connections online. As their teacher I feel it is important to share the information I have researched and the work of the above mentioned data portrait artists. We could discuss the importance of considering the type of information that is appropriate to share. There are a number of questions we could address. What are the things you want other people to know about you? What are the things that you do not want them to know? Are you different in person than the online persona you are creating? Having students create their own data portraits using only information they have shared online could open up even more discussions and possibilities. Or they could create a data portrait of a friend using a pseudonym or of a sports figure or a musician. While I feel I have only touched the surface of this issue, I believe this is a start in the right direction in helping my students realize the importance of understanding data portraits.

References

Felton, N. (n.d.). Biography. In Feltron.com. Retrieved from http://feltron.com/about.html

Frick, L. (2016). The future of data about you. Lauri Frick. Retrieved from http://www.lauriefrick.com

Kristin McIver: data portraits. (2015). Royal projects: contemporary art. Retrieved from http://royaleprojects.com/exhibitions/kristin-mciver-data-portraits/

McIver, K. (2016). The Selfie Project. Kristin McIver visual artist. Retrieved from http://www.kristinmciver.com/display.asp?entityid=10235

Thompson, C. (2007, May 22). The invisible man: an FBI target puts his whole lifonline. Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/2007/05/ps-transparency/

Urist, J. (2015, May 14). From paint to pixels. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/05/the-rise-of-the-data-artist/392399/

Weiskopf, D. (2014, July/August). Picturing the self in the age of data. Art papers. Retrieved from http://www.artpapers.org/feature_articles/feature2_2014_0708.html

Zwerdling, D. (2013, September 30). Your digital trail and how it can be used against you. NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2013/09/30/226835934/your-digital-trail-and-how-it-can-be-used-against-you

| mccullers_globalresearch.pdf |